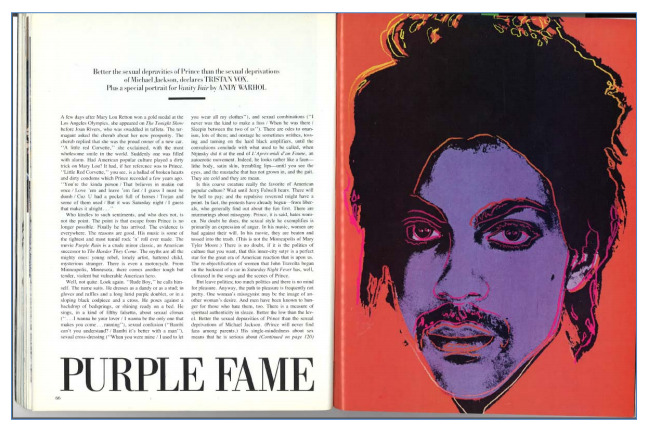

Andy-Wharhol-Foundation-The-Genius-of-Prince

There is a case at the Supreme Court that has the potential to completely rewrite how fair use is analyzed. At stake is the ability of artists to use each other’s works in creating new work, such as parody. On the one hand, artists should be granted broad leverage to express themselves, including commenting on each other’s work by using parts of it. On the other hand, artists should be fairly compensated for their work, and a large company swooping in to make minor changes to a work of art and then presenting it as their own without compensating the original work’s artist is wrong on a fundamental level.

Often, the most important question in an analysis of fair use is whether the secondary work is “transformative” and thus different enough that it should be considered within the First Amendment rights of the secondary work’s artist. In this case, the Supreme Court will be doing a thing that the courts are incredibly hesitant to do: comment on whether a work of art is “transformative” and why breaking the usual court taboo on evaluating art. This has always been a nebulous analysis, even with prior court guidance, and has the potential to completely shift the legal landscape of the arts and entertainment industries.

Fair Use

Fair use is, in essence, a First Amendment freedom of speech argument that an artist needs to take some material from another artist and is an exception to infringement under the Copyright Act of 1976 (which currently controls copyright law). The clearest example of this necessity is parody: for parody, a certain amount of taking must happen to associate the new work of art with the original.

While this is being debated on visual media in this case, this principle applies to all media protected by copyright, such as a song that another artist may sample in theirs. One of the most high-profile cases was around a parody of the Pretty Woman song in Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music, Inc., where a song parodying Pretty Woman had lyrics about the tough side of being a streetwalker. This case is cited by both sides in the Andy Warhol Foundation (AWF) case.

Fair use is currently decided by analyzing four factors:

- The purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes (in this case, the purpose is arguably an artistic image of Prince, or visual media more broadly);

- The nature of the copyrighted work (i.e. if it’s factual, you cannot copyright facts, but you can copyright how they are presented, like how names and numbers are arranged and displayed in a phone book);

- The amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyright work as a whole (did you take the entire image, or just Prince’s head, and how important to the original image was that head?); and

- The effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.

The first factor, the purpose, and character of the use is often the most important. This factor allows for “transformative-ness” to alter a work enough so that, even though the essential elements of a work are clearly being recreated, the secondary work is not infringing.

Background of the Case

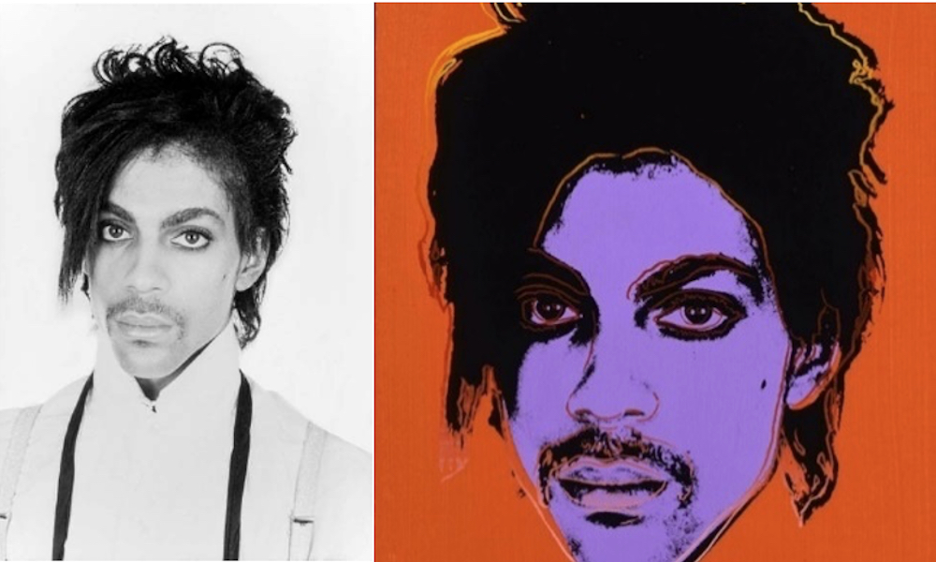

Prior to his death, Andy Warhol, famous for his Pop Artwork, painted an image of Prince using a photograph of the singer taken by a photographer named Goldsmith. During the photoshoot, Goldsmith assisted Prince with his makeup, posed for him, controlled the lighting, and made all the artistic contributions one would expect of a photographer. Prince looked like a vulnerable person in these photos, bringing his humanity to the surface.

Like much of Pop Art, Warhol used Goldsmith’s photo of Prince to build the painting around, similarly to how he did for his most famous paintings. This is typical of Warhol as his most famous painting, Shot Marilyns, was a silkscreen print based on a photo taken of Marilyn Monroe as a promotion for her film Niagara. He altered the color and a few other details of the image, making several images of Marilyn on one painting with different colored backgrounds. This painting has sold several times, garnering nearly $200 million in one sale.

When the painting of Prince was completed, it was dubbed “Purple Fame,” with Prince displayed as a larger-than-life persona, arguably making a point about the dehumanizing nature of celebrity. It is worth mentioning at this point that this would be different than “parody”: parody would make a point on the original media, whereas this is more of a general concept that doesn’t necessarily require taking elements of Goldsmith’s photo.

Goldsmith still owned the copyright and saw that the finished painting of Prince by Andy Warhol was being used as a cover for the magazine Vogue. The essential elements of her photo are clearly still present in the painting. Upset at not being compensated for the use of her work in what she saw as an infringing derivative of her photograph, she sued.

Case History

At the Second Circuit Court, the last stop before the Supreme Court, the court held that:

“… whether a work is transformative cannot turn merely on the stated or perceived intent of the artist or the meaning or impression that a critic – or for that matter, a judge – draws from the work. Were it otherwise, the law may well ‘recogniz[e] any alteration as transformative.’… as we have discussed, the court must examine how the works may reasonably be perceived… the judge must examine whether the secondary work’s use of its source material is in service of a ‘fundamentally different and new’ artistic purpose and character, such that the secondary work stands apart from the ‘raw material’ used to create it. Although we do not hold that the primary work must be ‘barely recognizable…’ the secondary work’s transformative purpose and character must, at a bare minimum, comprise something more than the imposition of another artist’s style on the primary work such that the secondary work remains both recognizably deriving from, and retaining the essential elements of, its source material.”

In its analysis, the Second Circuit contemplated the change in meaning but clearly stopped short of allowing a subjective intention of the artist or interpretation by an audience to become a dispositive factor. The Andy Warhol Foundation (AWF) appealed, and the Supreme Court accepted the case.

Arguments

AWF has been making an argument that the new meaning, specifically that turning the vulnerability of Prince in the photo on its head and portraying him as a larger-than-life icon to comment on the nature of celebrity, makes the image transformative. They also argue that the recognizable elements should be disregarded as fair use specifically protects infringing works, and that recognizability should either not be contemplated or not given as much weight.

AWF also repeatedly makes the argument in its briefs that the Second Circuit test expressly forbids contemplating new meaning in work, which honestly seems to be a bit of a bad-faith argument.

While the first part of AWF’s argument is interesting and exists within the acknowledged nuances of copyright law, the latter argument is so poorly made that it seems to undercut the first by its low quality.

All in all, I’ve been severely disappointed with AWF’s arguments: they certainly have a good point for fair use with the change in meaning being a 180-degree change: should the first factor ever be dispositive in an analysis outside of a direct parody of the original work, the AWF all but necessarily win their case.

However, they are going with a far broader argument in what appears to be a poor attempt at impact litigation that any new, subjective meaning places a copyright’s execution into question. This may be due to the Andy Warhol Foundation wanting its artists to be able to infringe more without legal consequence, or an ideological outlook that nothing should be off the table for appropriation artists following in the steps of Warhol. This argument may kill amongst art school students, but falls entirely flat for those not indoctrinated into appropriation art, and the amici briefs from Harvard law professors have been utterly embarrassing to the legal profession.

In summation, AWF wants the subjective intention of an artist or interpretation of an audience to be dispositive regardless of the amount of the taking of copyrighted material. The problem with this is that it sweeps away much of the already-modest guidance the courts offer on fair use, places the derivatives market into question, and provides less certainty to artists looking to use another’s work for their raw materials; even if more taking was a legal possibility, there would be a lot more areas of legal ambiguity that many artists would feel uncomfortable working in professionally.

The Goldsmith side has been far more focused, agreeing with the Second Circuit that subjective intention, meaning, and interpretation have their place, however, are not dispositive in the analysis. Goldsmith summed up their argument well in their most recent brief, stating that AWF is arguing for an “any-new-meaning” test rather than the test that the Second Circuit and previous courts have applied.

Stay Tuned

This case will deeply impact everything from the largest derivatives on the market, such as the multi-billion-dollar Marvel Cinematic Universe franchise, to the modest sketch artist contemplating their next project. The certiorari and follow-up briefs have already been filed and are available to view on the SCOTUS Blog. Oral arguments will be made in October, and we can expect a decision most likely in June 2023.

Thumbnail Credits: Andy Warhol Foundation

Sources

This is an opinion piece by Attorney Ryan Campbell.